I’ve always taken it for granted that the number of people on the planet was steadily rising. Where did I–where did we—get that impression? The sources have been all around us, some hidden in our vocabulary: “millions” of viewers watching television by the end of the 1950s; the two “superpowers” in a Cold War; Paul Ehrlich’s warning in The Population Bomb in 1968 about “overpopulation.” And population growth seemed to go hand in hand with prosperity—longer lives, bigger cars, more schools, jobs, houses. Even Africa, poor as it was, was said to be “teeming” with children.

This impression of growing numbers was in fact accurate. In 1950, the number of people on earth was 2.6 billion. Today, it’s about 8 billion. By 2060, it will reach about 10 billion.

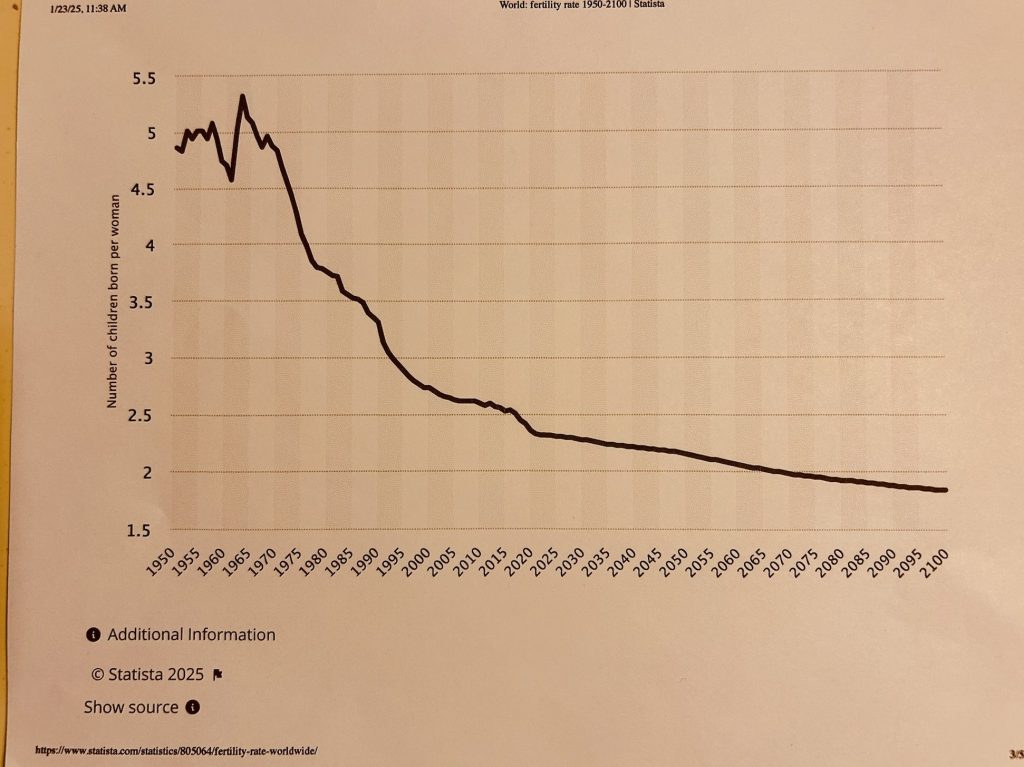

But that surge will end. Within about 60 years, the next generation will live in a world with a shrinking or static population instead of a growing one. This about-face in the bustling accumulation of our species is unsettling to me–and maybe to you. Nicholas Eberstadt introduces it this way in “The Age of Depopulation: Surviving a World Gone Gray,” (Foreign Affairs, Nov/Dec 2024): “For the first time since the Black Death in the 1300s, the planetary population will decline….What lies ahead is a world made up of shrinking and aging societies….A revolutionary force drives the impending depopulation: a worldwide reduction in the desire for children….[T]he total fertility rate for the planet was only half as high in 2015 as it was in 1965….[E]very country saw birthrates drop over that period” (42-43).

In a stable population, women give birth to an average of 2.1 babies who will replace the two adults who produced them. In earlier times, because mortality ran so high, fertility rates were much higher: six children in the ancient world, seven children in America in 1800.

Today, the fertility rate in the United States has tilted the other way. It is 1.6, higher than in many developed nations but still well short of the 2.1 replacement figure. In the blunt words of a New York Times editorial on immigration (1/10/2025), “America needs more people. Americans no longer make enough babies to maintain the country’s population.” We sustain our population at the current level only because immigration has been high.

Why do fertility rates drop in the first place? Less infant mortality, wider access to contraception, higher rates of literacy, increased status and participation in the work force for women—all have played a part, according to Eberstadt. So have the declining participation in organized religion, the increase in nonmarital unions and the valuing of autonomy, and the widening acceptance of small families and people living alone.

Such influences are especially strong in developed countries, where people live longer, the workforce shrinks, and home buyers are fewer. As of 2022 or 2023, the fertility rate has fallen to 1.26 in Japan, to 1.2 in Italy, to 1.9 in France. Even In sub-Saharan Africa, where the fertility rate was 6.8 in the late 1970s, it is now 4.3.

What about the world as a whole? As the Statista chart shows, the current global fertility rate is 2.3. It will reach 2.1 around 2060. The world’s population total (as opposed to the fertility rate) may follow the timetable of the fertility rate or it may drop more slowly as more people live longer. “The consensus among demographic authorities today,” Eberstadt writes, “is that the global population will peak later this century and then start to decline. Some estimates suggest that this might happen as soon as 2053, others as late as the 2070s or 2080s” (50).

What changes can we expect? Is this bad news, good news, or both? For those who worry about where our relentlessly growing world population could take us, the news of a decline may feel welcome. But for those who already know first-hand the shortages of medical assistants or home health aides for an elderly family member, the news might not come as a surprise.

Nicholas Eberstadt, who is an economist, makes predictions in his “Age of Depopulation” article. Families will “wither” (Eberstadt’s word) and will face the brunt of the dilemma of finding care for the elderly and those with dementia. On the whole, though, continuing prosperity in a smaller world will depend on whether governments and societies pivot flexibly in the face of the new demographic reality. One test of this flexibility will be an issue we are already familiar with: immigration.

Immigration will matter even more than it does today….Pragmatic migration strategies will be of benefit to depopulating societies in the generations ahead–bolstering their labor forces, tax bases, and consumer spending while also rewarding the immigrants’ countries of origin with lucrative remittances. With populations shrinking, governments will have to compete for migrants…Getting competitive migration policies right—and securing public support for them—will be a major task for future governments. (56-57)

We have a lot to think about and talk about. So will our children.

Source Note:

Three sites offer extensive data on current and anticipated populations and economies:

- The United Nations site on world population: population.un.org/wpp.

- Statista. Market and industry -related statistics for companies worldwide: statista.com

- Census data on many aspects of the U.S. population: data.census.gov